Photography by Steph Goralnick

One of the most provocative and memorable talks at the 11th (and last) annual gathering of the Cusp Conference in 2018 was by Christine Gaspar, the Executive Director of the Center for Urban Pedagogy—“a nonprofit organization that uses the power of design and art to increase meaningful civic engagement particularly among underrepresented communities.” Here, she gives her opinions on her organization’s community-driven work that rigorously fuses research, design and activism, including her insightfully grounded lens on the overly advertised quality of “empathy” in the design community.

Since 2011, you’ve been a fan of the Center for Urban Pedagogy (CUP)—how did you discover this organization and their work?

I first came across CUP at an exhibit at the Storefront for Art & Architecture in 2001. It was about building codes. I was in grad school for architecture and urban planning at the time, and saw a blurb about it in a magazine (maybe “Metropolis”?) So the next time I was in New York, I checked it out and fell in love with the combination of seriousness of the content (“Building Codes Save Lives”) and the playfulness of the presentation. I started following CUP’s work after that.

Fascinated by the fact that the Center for Urban Pedagogy states design as is: design. Not people-centered design, social design, civic design, among a great many other labels. Would you qualify the kind of design work you do? If so, how?

I love this question! I think we do modify it in various ways in different contexts, and I think the most common way I personally describe it is probably as “community-engaged design.” But I mostly think the labels are pretty unsatisfying and don’t quite get at the values we care about. At its heart, I believe that good design IS design that brings people into the framing and understanding of problems, and into the shaping of solutions. So in that way, design is adequate.

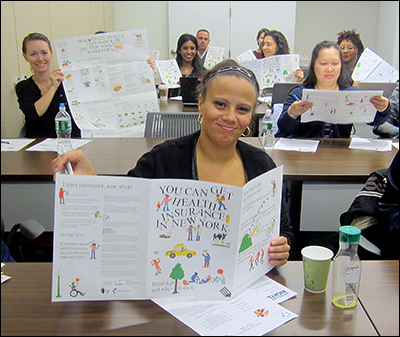

Center for Urban Pedagogy project “Figuring Out Health Insurance”—“illustrates how health insurance works, basic rights under the Affordable Care Act, and how to get insurance—including reduced price programs.”

Your talk at Cusp Conference 2018, Chicago, reinforced the importance of making the complex clear. Who, past/present, do you view as motivational examples of this human act?

Personally, I’ve always had a fondness for children’s books and feel like the best ones can really convey so much with an economy of words and images. (One favorite that comes to mind is “Popville” by Anouck Boisrobert and Louis Rigaud which has no words.)

I think an obvious precedent for CUP is the “Schoolhouse Rock!” series from the late 70s which used songs and animation to make opaque topics, like how legislation works, both understandable and memorable and maybe even a little fun.

The work of Otto Neurath (1882–1945) is an important touchstone as well. His ideas really resonate with CUP’s model, too, in that he saw his role as a “transformer” that would bridge between, on the one hand, the social sciences and the data they generated and, on the other, the public and its understanding of how that information affects them. He really believed in the power of images to convey meaning regardless of one’s literacy or level of education. He said, “Whenever the fate of individuals and communities is at stake, we need some comprehensive knowledge to help us make our own decisions. It is for this that I think visual aids are so important, especially when we wish to educate ourselves and others in citizenship.” I think I pulled this from “Otto Neurath: The Language of the Global Polis” (2008) by Nader Vossoughian, published by the Netherlands Architecture Institute. That feels very aligned with what we do and why.

The composition of CUP teams—artists, designers, educators, activists, researchers—is awesome. What are some don’ts in managing multidisciplinary collaboration?

Don’t let your ego get in the way.

Don’t confuse interdisciplinarity with “we all do all the things.” There is this trap that some collaborations fall into. I also think it’s how some people unfairly knock participatory design processes, claiming that having untrained people do the design work weakens it. The trick of good interdisciplinary collaborations is to have clear roles and expectations, and to create a strong framework within which each person can do the thing they’re really good at, and contribute to moving the project towards its goals. You get more than the sum of the parts if you do it that way. And it’s important to question what we count as “expertise.” Often, people who are the target audience and can give the most important information about existing problems or how something should work are not seen as having equivalent expertise to trained designers—and that’s just not the case. Lived experience is real expertise, and no designer however well-trained can adequately solve a problem without the contributions of that expertise.

Don’t underestimate the importance of the mundane: scheduling things, following through, setting clear goals and deadlines, defining roles clearly. These are the things that you never read or hear about but they’re the things that make projects successful. They allow for the creation of trust and they make it so everyone can focus on their work.

Don’t assume everyone has the same reference points or understands the same jargon. Diversity of experience is actually a great thing. But if you don’t address it by finding a way to create a shared language and process, it can derail a project.

Based on your masters work, how does architecture and city planning feed/influence your work?

I’m not sure how to disentangle that from how my brain works! I also have a background in policy and I spent a lot of my undergrad education thinking about how policy gets written, why and then how it plays out on the ground. The combination of that with architecture and urban planning helps me think about the issues we work on at different scales, and helps me link the larger conceptual understanding of them with the more practical understanding of how things work in the day to day. My architecture education helped me develop ways to be creatively productive and not so precious about my work as I’m creating, and gave me a lot of practice at visual communication. My urban planning education helped me understand interdisciplinary collaboration and gave me lots of technical skills. But I think it’s my liberal arts education that helped me understand how to break down complex things and communicate clearly with words. My undergraduate program in Environmental Studies at Brown was also really grounded in the communities of Providence—and we did a lot of participatory action research and work with communities that to this day informs my understanding of how to work with communities you are not a part of in ways that are respectful.

I also draw a lot on my own experiences as the child of immigrants. So many of the projects I’ve worked on address things I saw happen firsthand to my family, especially to my mother, who was a domestic worker. I was often given complex material and asked to help her understand what it meant because I could read English better than her, even though I was just a little kid. That plays out in families every day and is the kind of context we really think about in our work.

I don’t mean to be overly critical of architecture, but in some ways I think architectural education’s biggest impact on my work is in giving me examples of the ways I don’t ever want to work. For a supposedly forward-thinking field, architecture is so regressive in its practices. It’s still so misogynistic, it’s still so white and privileged. I always struggled to find my place in it, and I was often made to feel explicitly excluded from it. But at some point, I realized that I just totally reject the idea of the heroic exceptionalism that contemporary architecture education is predicated on. I still have very strong ties to architecture, but most of them come in the form of working with other individuals who have gone on to shape careers in some form of socially-driven work and who have similarly shaped their practices as rejections of that model of practice. (I got to work with some of them to create this.) I do think architecture is an amazing field, and I really appreciate how it gave me tools to think about looking at the world and creating new things. I’m excited to see what it can do when it makes room for more voices.

Center for Urban Pedagogy project “What Is Zoning”—“the toolkit includes a set of activities that break down density, bulk, land use, and how proposed rezonings could affect neighborhoods.”

Stemming again from your Cusp 2018 talk, your push to replace empathy with accountability was positively provocative. Can you restate and expand on this dynamic? How can people, particularly designers, work in a truly accountable manner?

My beef with “empathy” is that I think it’s become distorted and used as cover for some pretty bad practices. In my talk at CUSP, I referenced an article I had just read in which a designer was arguing that a great way to build more empathy into one’s practice was to do this activity where you imagine what someone else is feeling in their day-to-day life. He gave the example of a barista. I know this happens to be an extreme version of this idea, but he was basically doing the exact opposite of what a practice of true empathy would ask of you. He is trying, within the limitations of his own experience and privileges, to imagine what someone else might be experiencing without having any interaction with that person whatsoever. There is a profound arrogance in believing that you understand another person’s plight, even if you do get the chance to speak with them about it, let alone if you are just imagining in your own head. I likened this to the moment in which many thoughtful, progressive men over the last year or so were shocked to hear about all the pervasive ways in which the women in their lives accommodate, work around, or otherwise have to live with sexism and sexual harassment in their day to day lives. They couldn’t imagine this because it was so outside the realm of their own experience. They had to be told and shown over and over again that this was a real thing. If we rely on our own experiences and perceptions, as this designer above suggested, we perpetuate our own biases but also our own blindspots.

I’m arguing for a recognition that empathy means something specific and that we don’t ever truly have “empathy” for another person’s plight. We should still work to understand it, though, and we can only do that by talking to or otherwise directly engaging with those people and learning about their experiences. We have to have the humility to understand the limits of our own knowledge and to recognize the strength and power of that person’s expertise about their own experience—and our need for that expertise to inform our work.

That means we don’t get to imagine their experience in our own bubble and then imagine how we might design to solve some problem we perceive them as having. It means engaging them in the design process, paying them for their time because it has value to the work we are doing, and understanding that you’re not going to “fix” it for them or “save” them, but that the best you can do is stand beside them and join your resources to theirs and work together to make change.

I think that accountability can be built into the work. We try to do that in a bunch of different ways at CUP, and I think we could be (and are working towards) doing more. We have stakeholders from the communities we serve be (paid) jury members to help us select projects; we have criteria we use to select projects and we make that public so people know how we are selecting and can hold us accountable if we fail to meet those goals; we have a methodology that always brings members of impacted communities into the design process and we pay them for their participation; we have a deeply collaborative process that requires not just CUP’s sign-off to be complete, but also the community organization we’re partnering with and the designer; and we do evaluations of our process with our partners at the end of each project to make sure we understand how we could be doing better.

In a way, what I’m arguing for is for design projects that are socially motivated to have a clear articulation of whom they are accountable to and how. I see a lot of work that is about certain target audiences, but the way the project is funded and structured, and who gets to make decisions about it suggests that the design team is accountable to an entirely different set of people.

I remain curious about the term “design methods.” I admire CUP’s collective practice of them, from stakeholder interviews/workshops to prototyping—to drawing (more on this later). Though practiced a lot, it’s not popular to say, even claim, compared to the ever-popular term of “design thinking.” How do you select which design method(s) to use per project?

We think of our process as being a coherent methodology, with a bunch of interconnected parts, and then we make adjustments to the particular techniques we employ based on the specifics of the topic or our partners. For example, we usually do some sort of stakeholder research at the beginning of the project with members of the target audience, but in one project we do that through one-on-one conversations because our partner is a direct service organization and we’re joining them in their client meetings; for another we do it as a focus group because our partner is leading a training session; and for another we do it in small groups because the target audience is children in foster care and we need to meet with them with their caregivers. It’s really the specifics of the context that help us determine what’s appropriate, and then we try to work within those constraints.

Many of the techniques we use are ones that people associate with “design thinking.” But we don’t frame our work that way because we’re trying to frame it in around the way we work with our partners, which design thinking doesn’t take a stance on. For us it’s the accountability pieces and the relationships that are core to the methodologies.

One of my favorite quotes is by the novelist Kurt Vonnegut: “Another flaw in the human character is that everybody wants to build and nobody wants to do maintenance.” What are activities that you and your team do to maintain the relationship with clients after recommendations/results are made?

I love this question, too. I feel like we are really into maintenance. We have ongoing relationships with almost all of our former project partners, whether through our regular check-ins to see if they’re still using the project and what impacts it’s having, or through other projects with them, or through collaborating with the organizing networks they’re part of. Many of our partners use not only the tool we created with them directly, but other ones we crated with other organizations. So it’s a real ecology we’re part of. It’s another way we continue to be accountable to our partners. We keep seeing them, and we have to live with the reputation that our work with them creates for us.

How would you describe CUP’s work culture? How do you and your team keep your work culture going?

It’s very collaborative. In our projects but also in our decision-making about a lot of things, including how we hire. We have a lot of conversations about how we are doing things and how we could or should be doing them.

It’s a little weird and funny. There is a lot of laughing when we are together.

We take a high level of care in our projects. There are lots of reviews and revisions. Not everyone is down for that but it’s important to us. It’s not about perfectionism; but it’s about ensuring that our partners can trust us to get things right so they can really use them in their important work. We don’t take that lightly.

We’re always trying to figure out how to do better. We constantly tweak things and we regularly talk about what we got wrong, what we could do better.

It’s also a really sane place to work. Our work is hard and we are all pretty wiped out at the end of the day, but everyone goes home after 8 hours. We have an actual 40-hour work week. I’ve worked really hard to make that happen, and it takes real commitment to do it. We see it as part of how we can be a more equitable organization. You can work at CUP and have a sane life, a family, an outside art practice, things that keep you whole and sane and not burning out, and that also make your work stronger. We might get paid a little less than if we didn’t do that, but I think it’s important.

Center for Urban Pedagogy project “ULURP” (Uniform Land Use Review Procedure)—“the process by which major land use changes get reviewed and approved in New York City.”

In doing the purposeful, collaborative and interactive work you do in demystifying complexity in public policy, how do you keep fit your creativity, critical thinking—your sanity too?

The truth is that the thing I find most grounding and nourishing these days is spending time with my husband and our three-year old. I guess it’s a cliché, but her joy at the smallest things and her lack of awareness of the worst things happening in the world are just really nice to get to inhabit if only vicariously. We read together a lot (see previous question about my love of children’s books), we cook together, and we go to museums. I don’t think I read as much of the didactic text as I used to at exhibits, but I really get to see them in a new light.

I had stopped reading anything non-work related for a while, but I’ve really come back to it and am enjoying reading fiction again. If I’m totally honest, though, my husband and I often drown our sorrows after a bad news day by watching “Nailed It” until we’re crying-laughing.

What’s your media diet like? Who and what do you recommend to help be aware of current affairs/culture/your community and the world?

I sill pay for a “New York Times” subscription and think having professional journalism is critical.

Like all of us, I’m feeling really ambivalent about social media these days. For me, it’s kind of a mix of hearing about amazing cultural things, getting intense local political news from friends around the country, and also for hearing opinions I really disagree with from people in my family and friend circles with whom I diverge politically in a pretty strong way. It makes me grit my teeth, but I try to stay out of my own bubble. I mean, the truth is that most of my Facebook feed is amazing, strong, hilarious, thoughtful women of color talking about art, social justice, or art and social justice. So that keeps me coming back. I also resisted Instagram for years but finally gave in and my feed there is 100% illustrators, and it’s kind of a soothing space for me. I pop in and out of Twitter, but mostly through work or things my husband forwards me about football.

I also read a bunch of newsletters regularly, some local New York City neighborhood based stuff, but also Nonprofit AF, AIGA Eye on Design, Next City and the newsletter from the Furman Center at New York University (a roundup of recent news about planning, land use, real estate), Grain Edit, among others.

I’ve gotten into podcasts in the last year (after my husband started hosting one and I kind of had to get with the program). WNYC’s investigative series, like “Caught,” “There Goes the Neighborhood” and “Aftereffect” are amazing and tell really important, complex stories that intersect with a lot of the work we do at CUP. I love “Still Processing,” “2 Dope Queens” (I’m listening to the Michelle Obama interview on repeat), “Ask a Manager” because I’m always working on that part of my skill set, “Respectful Parenting” because I’m also always working on that part of my skill set, “99% Invisible,” “The Vocal Fries” (about linguistic discrimination; I highly recommend the “They/Them/Theirs” episode), “Dr. Gameshow” for laughs, and the “Splendid Table.”

With being in these politically-charged times, how are you coping and channeling what’s happening into your design work?

In some ways, I think it’s easier to process what’s happening for folks who already work in social justice spaces, partially because all of the things that are happening we already saw happening, they’ve just intensified; and partially because going to work every day feels like a way to fight these things happening.

That said, the work we’ve been doing has gotten a lot heavier for a bunch of reasons. We’ve been working on projects for audiences like parents at risk of deportation trying to set up guardianship for the kids, or children who are victims of crime and have to testify in court. It’s a lot. One of our goals for this year is to learn more about vicarious trauma and how to process it. It’s something that people in direct service fields like social work have been doing for a long time and that we can really learn from.

In terms of channeling it into our design work, I think we’re increasingly more conscious of the ways we collaborate with folks and the ways that design contributes to or disrupts oppressive ideas and narratives. For example, we see a lot of stereotypes often unthinkingly perpetuated in illustration. It’s something we talk a lot about in our projects; things like how racial or ethnic signifiers might be presented or how illustrators often default to one body type/size/proportion, or how ideas about gender are presented. The assumptions that get packed into design work can be harmful if they’re not interrogated.

In your creative work-kit, what are your go-to tools, the ones you love using because they prove reliably effective?

I don’t know that I have really good answers here. I love a notebook and a pen. I am an obsessive list-maker.

Naming game: what’s the non-erudite version of the Center for Urban Pedagogy?

Oh man. I wish I had a good answer for this one. I think I’m too close to it. I don’t know how many times I’ve told someone our name and they’ve just said, “That’s terrible.” But the thing that’s really won me over about it is that, when we talk to community organizers, they almost immediately make the connection to Paulo Freire’s “Pedagogy of the Oppressed” (1970) and it helps ground our work in something that’s relevant and meaningful to them. I think it buys us credibility in a way. And then when we work with community members, they really just think of us as CUP, and what’s more accessible than a simple household object?

How does New York City contribute to your work? And what makes it special for startups/business/creativity-at-large?

Well, we work at the intersection of design and social justice, and in New York City we have access to so many incredibly skilled designers who want to collaborate on meaningful projects. At the same time, we’re in a city with an incredibly rich and robust community organizing culture. There is so much important organizing history here and a real sense in the communities that we work with that organizing matters and that it can lead—and consistently has been the thing that has led—to meaningful social change. Our work exists in support of organizing work, and without that, I don’t think we’d have been able to develop this model.

Speaking of New York City, congratulations to you and CUP on your partnership with the Drawing Center in participating in their annual Winter Term series of creative programming in 2019. How did the relationship originate between CUP and the Drawing Center? How is drawing critical to CUP’s continued success?

The Drawing Center reached out to us last year about participating in Winter Term, and we were really honored and excited. I think almost everyone on staff was already a fan, and because we spend so much time in social justice and community organizing spaces, I think we’re always genuinely surprised when folks in the art world recognize our work as part of their world, too.

It’s also exciting because we got to overlap with some folks from The Drawing Center last year when our organizations were both participants in an initiative to help introduce more anti-racist practices into arts organizations—The Race Forward Arts Lab. Knowing that both of our organizations are committed to those values made it even more meaningful to be collaborating with them.

Opportunities like this are not ones we usually seek out (mostly because we don’t have the time or resources to), but they’re really important for us. They help us tell our story and share the work that we do with broader audiences. We’re a little bit like that saying “the cobbler’s children have no shoes.” We work with all these organizations to create visual explanations of really complicated issues, but we’re pretty bad at doing that about our own methods! This exhibit is an opportunity to do that and it helps us keep reaching out designers who will want to collaborate with us on future projects, as well as helping to share some of what we’ve learned along the way with other folks who want to work in similar ways. It’s not the kind of thing you can apply for a grant to do, but it can have major impacts for us as an organization.

• • •

All images courtesy of Christine Gaspar.

• • •

Read more from Design Feast Series of 104 (so far) Interviews

with people who love making things.

🖐🏾 Donating = Appreciating: Design Feast is on Patreon!

Lots of hours and pride are put into making Design Feast—because it’s a labor of love to provide creative culture to everyone. If you find inspiration from the hundreds of interviews, including event write-ups, at Design Feast, consider becoming a supporting Patron with a recurring monthly donation.

Help keep Design Feast going and growing by visiting my Patreon page where you can watch a short intro video plus view my goals and reward tiers, from $1 to $12—between a fun souvenir and a satisfying brunch.